The High-Effort Tyranny of “Have you tried turning it off and then on again?”

Please excuse this box full of uncharged devices.

In the early days of Evernote we used to say our biggest competitor was paper and pen (this undoubtedly originated from Phil Libin). It’s one of the reasons the product’s early integrations with tools like Livescribe and our partnership with Moleskine made so much sense. By embracing that analog competitor, that study in simplicity, we gave ourselves a bar in how we designed and imagined the product, an aspiration to be as easy to use, so that the act of committing anything and everything to memory was as frictionless as possible.

While the pen and pad were mainly aspirational (and I’d like to think we landed a few very beautiful, relatively frictionless experiences in our time) the metaphor also highlighted the complexity we inevitability introduced compared to our analog predecessor.

Buying stuff, jogging, watching tv, board gaming, meditation, cooking toast — every “thing” you can possibly do has received a tech-based fine-tuning and many devices offer up internet connectivity. Most of these products are positioned as a new way to succeed at your chosen pursuit (professional toasterers exist!), but in most cases they’re optimizing very little.

The tradeoff between this optimization and what’s required to manage the application may not add up.

Everything Has An Effort Curve

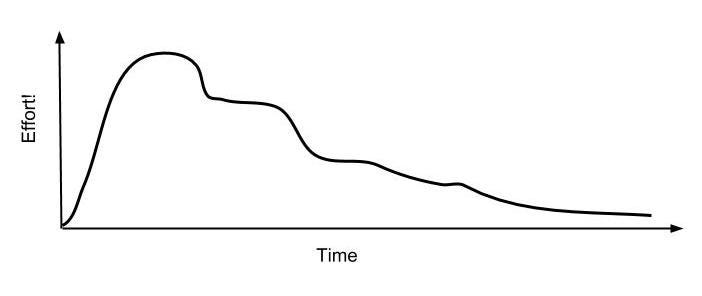

Think of any activity, any “thing” that you regularly do. In the beginning you don’t know what you don’t know and you have to learn. This is a high effort period with lots of fits and starts. Then you begin to optimize the activity. You learn new ways of doing the activity, you get better at it, and it becomes a habit. The effort level gradually drops, with a few “aha” moments serving as steeper drops along the way down. Your curve may jump up as you challenge yourself with new high effort versions of the same activity, but eventually your effort curve ends up looking like this:

Success! Time has taught you a new skill and you are now able to do the work with little effort.

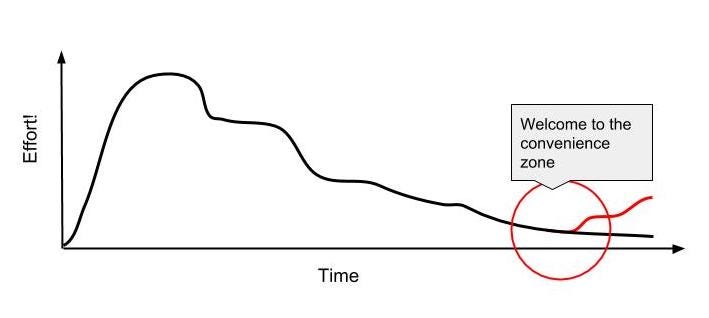

Setting aside major technological advances that introduce completely new ways of actually doing the activity, most new technology operates at the very end of the effort curve: the“convenience zone.” These products succeed at taking minor activities (things that you’ve gotten good at through time and practice) and making them slightly more convenient.

The danger of optimizing activities in the convenience zone is that the gains afforded by the application are minimal at best compared to their potential tradeoffs. Much ink has been spilled on the topic of trading privacy and personal information for convenience. One other less pernicious but accretive tradeoff involves the complex systems it takes to deliver this convenience. These systems may in fact increase the effort curve, taking us away from our low effort activity and riding that red line in the figure above.

The Ecosystem of Effort from IoThing Tracking

What does the effort of a complex system look like?

Let’s take an exercise-based IoThing Tracker. It tracks your physical activity, some basic health data, how often you do it, and perhaps sleep patterns. It accumulates data that points to success or failure of your daily routine, but it (crucially, much to our collective chagrin) can’t exercise and sleep for you. At best, it provides data that may be motivation to exercise more or improve your sleep hygiene. At worst, it is effectively telling you what you already know: that you sat in a chair all day long. Regardless, it is operating at the tail end of that effort curve, providing a convenient way to track your activity.

For the IoThing Tracker user, the question then arises: what is the true cost of this device, in terms of time and effort? Many IoThing Trackers are beautiful devices with a host of useful features. But what is the weight that comes with owning these devices? What are the systems that underpin the thing that I’m now officially tracking?

Here’s a list the potential requirements to make a IoThing Tracker work.

- Internet

- Bluetooth pairing

- The IoThing’s website, which requires a username and password or SSO through Google, Apple, etc.

- Your account on their website, with your personal information

- If you want to not reuse a password, a password management application

- An iOS or Android app to sync with (that needs to be kept updated)

- An iPhone or Android device (that needs to be kept updated)

- The battery inside the IoThing Tracker

- Charging cable for the IoThing Tracker

- Your brain, required to remember to charge the IoThing Tracker as often as necessary

- The inevitable lanyard, band, or object that tethers the IoThing to you in a special way that is hard to replace

- The IoThing Tracker itself

This is the system of interconnected requirements for an IoThing Tracker user, each representing an independent point of failure. What it purports to solve with the complexity above is providing more measurement around exercise and sleep patterns for the person asking the question “how much am I really moving per day?”

The information it provides can be great for those focused on exercise or advancing their health, and for those where the act of tracking produces encouragement and engagement. But for the general consumer or for those already motivated and committed to the effort required for an activity, we should all ask ourselves if the technology applied here worth the additional effort? Are the improvements the service or application giving you enough to cede and rely on something that has so many requirements? Is it worth yet another account that must be managed?

Exercise, sleep, meditation, and more are probably the most personally beneficial of all things to track, because of the potential net benefit provided to those who opt in. But this effort analysis should equally apply to any connected device — wireless anything, internet toasters, refrigerators, watches, etc. Any SaaS + hardware related business is a potential addition to your at-home IT department requirements that should be evaluated as such.

You Are Your Own IT Department

There’s a reason our lives are littered with disconnected and uncharged devices. Raise your hand if you have a box of chargers missing their device.

Consider that managing the ecosystem above becomes a part of your daily routine. By opting into technology to support your activity, you are agreeing to ensure those items above are updated, charged, activated, and paid for. You allow them to become a part of your daily life, introducing a complex system for the convenience of improved data. Effort rises, and suddenly that shiny new gadget doesn’t look so shiny anymore.

Can you get that red line back down and enjoy the pleasures of convenience without the complexity? Maybe. You can help reduce some complexity by embracing even more tech (automatic payments, automatic updates, wireless charging, etc) but they only add to the potential complexity of the ecosystem that now supports tracking your daily steps.

Further, if anything in this system breaks, the tools (and accessibility) for working with and repairing these services as a consumer are not always readily available. At most you have access to a knowledge base article or two, both of which suggest checking your connection, re-installation, or restart. If rudimentary steps do not work, then you must call customer support, which will require additional time and effort.

Is the Product Really That Convenient?

Ultimately, customers and product creators must evaluate products not just on their merits and ultimate convenience, but also for the complexity and effort that will take to maintain that level of convenience.

For the product manager or creator —they should work to understand if the value of their product is being degraded by an excess in overhead. The higher that overhead, the less likely customers are retained. Understanding the ecosystem within which your product operates and what it ultimately requires to get the most from it is core to delivering a quality experience across multiple ecosystem types (lots of people are still on old phones) and planning for how best to fail gracefully. Understanding these dependencies helps you define a better base CX.

For customers — they must ask themselves before signing up for that new gadget or service: is the time spent managing and supporting the service, (particularly when it has an issue) worth the convenience they might ultimately receive from it? Will it help them achieve their goals, or are there hidden costs that will guide them away from and even potentially distract from what they originally wanted to accomplish in the first place? Will the device end up in a box in a closet with a pile of other devices that never outlasted more than a couple battery cycles?

Ultimately, we are melting away countless hours and spare neurons devoted to supporting the systems we have bought into, when quite often we will suffice without the technology. And so, before you consider buying into that next magic solution, consider that you never needed it to begin with.