Chronologically Reading David Mitchell's Uber Novel

Recursive currents flow just below the surface, delivering errant flotsam the size of a hulking ghost ship.

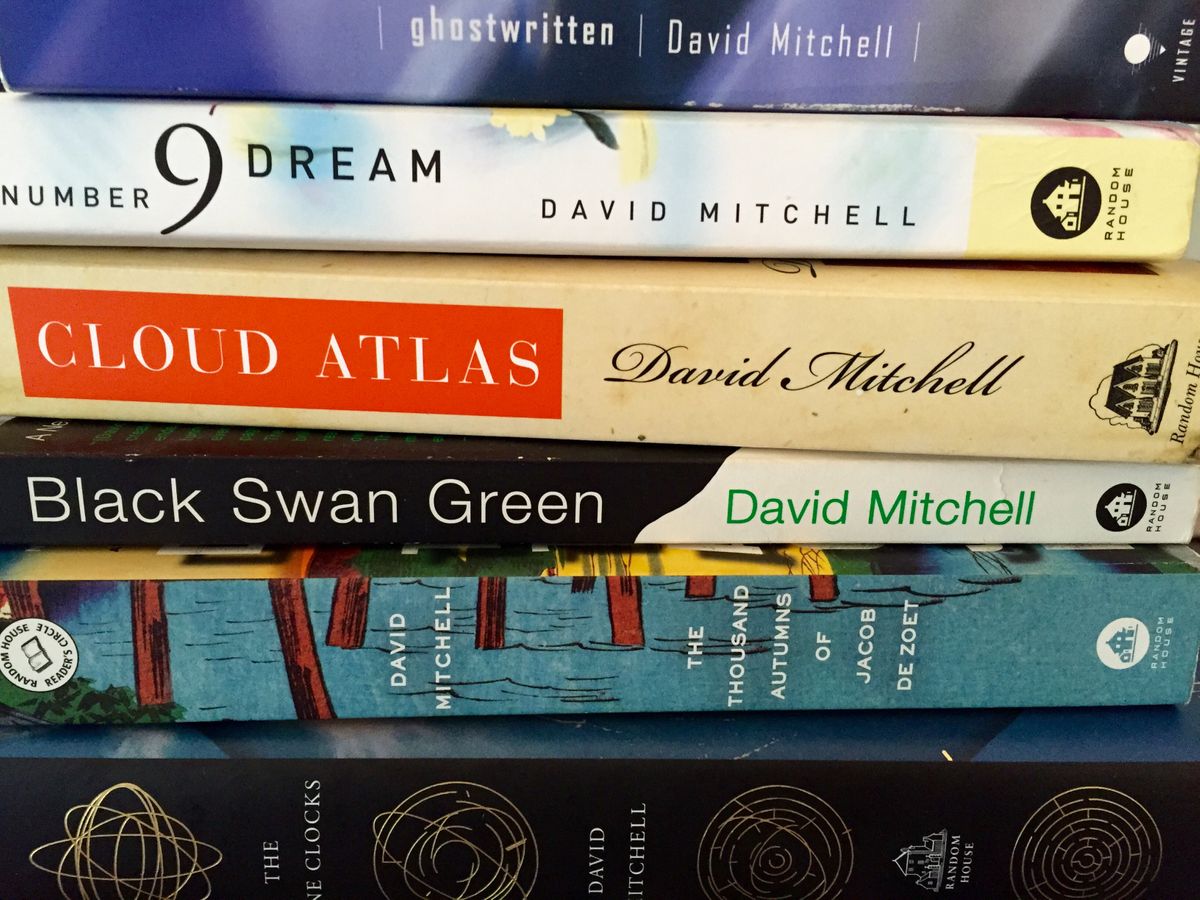

Early reviews of David Mitchell's sixth novel revealed that his collected works were fast becoming an uber novel. Until The Bone Clocks, it hadn't been abundantly clear that characters, the ancestors of characters, works of art, and other ephemera were beginning to reappear within Mitchell's novels in often subtle ways. I can't remember if "uber novel" was the author's choice description or loaded from an overbaked PR piece, but the idea intrigued me enough to investigate. Six books, a couple thousand pages. A worthy adventure. I ordered and/or found them and read them cover to cover in chronological order (I've yet to tackle Slade House, it's on the docket).

Chronological order now seems a joyful way to read someone. It forces a reckoning with the artist's biography. What was happening in their world and to them when they wrote this book? Why did they follow up book X with book Y? It feels like a more conscious and deliberate methodology, better than scanning best sellers, falling accidentally into interesting cover art, or giving in to Amazon's "customers who bought this also bought this" algorithms. Instead of picking up the next best seller, you lasso yourself to an author, pledge yourself to their lowest lows and their highest highs, and come out of the process with a better understanding of another human being and (quite possibly) an era.

After only six books and one author the idea is undoubtedly conjecture. The next few authors I choose should test whether or not this proves to be an insightful or thoroughly exhausting way to read - or both. Mitchell does not particularly have any lows. His first book, unpublished, was canned by the author and will never see the light of day. Vonnegut ranked his own history at one point, giving his books varying letter grades. There were enough C's and D's on his list that I daresay there will be a good deal of trudging involved. If it's Stephenson, I'll need to drag myself begrudgingly through Anathem, bathe in Cryptonomicon, and hold dearly tight Snow Crash.

Choosing an author has its benefits. I hinted above that I feel a deeper affinity with Mitchell - living with an author's words for months will have that effect. Mitchell has a fought a stutter since seven, and delving into Black Swan Green allowed me to grasp his shy, book-bound world at a young age. His eight years spent in Japan clearly appeared in elements of Ghostwritten.

One common barrier to reading more is not a question of time, but a question of what. Deciding which book to read is not a simple task, or undertaken lightly. You're giving over a significant length of time to someone's thoughts, and there's a near infinitesimal supply of books, all yammering away as you wander the stacks. Picking an author neatly skirts by this noise. The works come wrapped up in a box with a fancy bow, a gift of five to ten to fifteen books in tidy order.

Of course then you have to find the damn things. For long dead authors with prolific histories this is probably easier said than done.

But back to the uber novel, the catalyst for my dive into Mitchelldom. It's incredibly tempting to give the idea a sigh-heavy, deeply cynical eye-roll. Is he simply mining old content - or it is a marketing ploy? Is each reference an insidery wink-wink nudge-nudge to readers of his works, an easter egg that gives a nice endorphin kick to those who happen to remember just why Marinus in Clocks has a taste for Scarlatti's Chef's-d'oeuvre for the Harpsicord? We've become accustomed to meta-universes, and dreams within dreams, and twist endings. To decades of books and movies that weave asynchronous characters into a synchronous story. Whole universes, upheld by never-ending trilogies and reboots. An uber novel is just another rehashing of these same ideas, right? These days, you need a universe to make a buck.

If there is an u-novel lurking somewhere between the dad-addled imaginings of a Tokyo youth, the sun-dappled fields outside of Worcestershire, or the harbors of Dejima in 1799, it is far more elegantly constructed than something like the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Whereas the MCU is a mix and match game of heroes and villains, giant symbols clashing together bombastically across entire galaxies, Mitchell's u-novel presents a universe where seemingly random, recurrent details flit about vast stretches of time.

If time is generally experienced as a stream then Mitchell's world is an ocean. Recursive currents flow just below the surface, delivering errant flotsam to the reader, sometimes the size of a hulking ghost ship, sometimes a small patch of life giving kelp. These moments briefly connect, then float back off into the immense ocean. They may return. They may not. If they do, it may very well be centuries later.

Where character paths or past/future elements do meet, they are not crushed together by the God-like force of will of some outside author or director - think Paul Thomas Anderson's Magnolia. Rather, Mitchell's narratives are replete with all the necessary glitches of reality. Works of art reverberate over time long after their creator has committed suicide, and ancestors may reappear to have a limited and superfluous effect on another story line. How often do supporting characters from other stories truly affect our own? The references never feel like winks, but necessary complications of existence. The new friend I meet in twenty years will have known my brother's acquaintance from grade school, and we will both marvel at our world's smallness. I will have a chance encounter with a lonely drunk in an empty bar on a quiet evening in DC, and we will talk about Black Swan Green, because he drinks to drown out his stammers. We are all on the Prophetess, wondering what island will crest over that next horizon, even if our ancestors' ancestors have undoubtedly been there before.

Recurrent elements could not arrive without a successful delivery system. Rebirth, reincarnation, genetic memory. Cyclicality. The Bone Clocks (re)introduces a central character capable of reincarnating his soul 49 days later in the body of another recently dead human. Marinus, the same character from Thousand Autumns, has lived fifty something lifetimes, and runs with a team of characters who range from five to hundreds of lifetimes old.

There are less obvious delivery systems than full on reincarnation.

The central characters that drive the chapters of Cloud Atlas have a vague sense of one another across generations, through their works of art and the genetic connectedness of their telltale birthmark. These genetic memories exist as a tiny, imperceptible murmur to the character, like a sense of a déjà vu. In Ghostwritten, an unnamed character that felt not unlike one of Clocks' Sojourners, flits about from human to human, living in their memories and adjusting their actions. Whether or not that ghost was a Sojourner is another discussion, probably saved for an idle Sunday morning over coffee.

There is the cyclicality of destructive human choice. The tribal world of Zachry (the furthest into the future we have traveled thus far with Mitchell) exists in spite of the technological progression of Sonmi 451's reality, and resonates with the final chapter of Clocks, which finds humanity sliding back into the dark ages. Revolution rears its ugly head in nearly every story save Black Swan Green. The weak are literally consumed by the brutally powerful. The Anchorites decanting. Enomoto's sacrificial newborns. The Kona cannibals. Fabricants turned into cheap protein and Soap.

The advantage of this cyclicality is that endings and beginnings become largely meaningless. Stories end where they begin. If Mitchell is constructing an uber novel, it will never be fully defined in the way we'll inevitably attempt to define it. There will always be a not-fully-knowing, drenched in a shallow understanding but deep feeling of the world's interconnectedness.

It will most definitely be a continually surprising universe. Mitchell uses Thousand Autumns, a historical novel that required a single day of writing and research to accurately depict a single sentence, as the jumping off point for a reincarnating, soul-vampire battling doctor.

He reportedly has twenty or so characters rattling around in that brain of his, and they will undoubtedly contribute to his universe. But since we're talking a world of locations across generations, we'll likely be treated to the same interconnectedness, same disparate elements occasionally intruding themselves on our existence.

Now, and perhaps more importantly: who will I read next?